When most people think about multiple-necked guitars, they think of rock music — and probably heavy metal at that.

Images of wild rock stars with long, teased hair and zebra pants come to mind, wielding a skull- or devil-horns-encrusted multiple-necked guitar monstrosity, more for show than anything else.

In fact, Spinal Tap is the first band that pops into my head.

And while yes, mutiple-necked guitars (and basses!) do make for a good stage prop, they actually have been around for musical reasons for a very long time.

Renaissance musicians — the OG rock stars

The first multiple-necked guitars and lutes appeared in the Renaissance, as a matter of fact. These instruments, like their modern-day counterparts, had more than one neck that could vary in strings, length, tuning, and number of frets (including fretless), allowing the musician to quickly switch between or use two “instruments” at once.

One example of such an instrument is the contraguitar, which has a traditional fretted six-string neck and a second, harp-like neck fitted with lower “bass” strings. The player had to tune the bass notes according to the song being played such that they could pluck the correct note with their thumb, since there was no way to fret or capo the lower strings.

Instruments like the contraguitar are still in use today by classical guitarists, since composers wrote works specifically for extended-range instruments like them.

Modern multiple-necked guitars

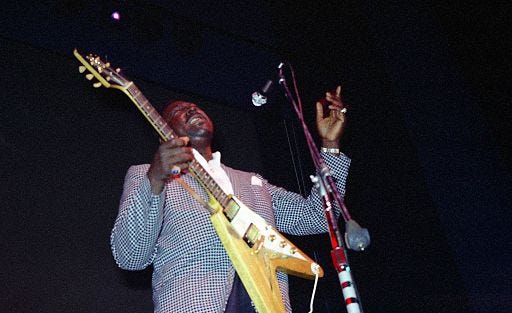

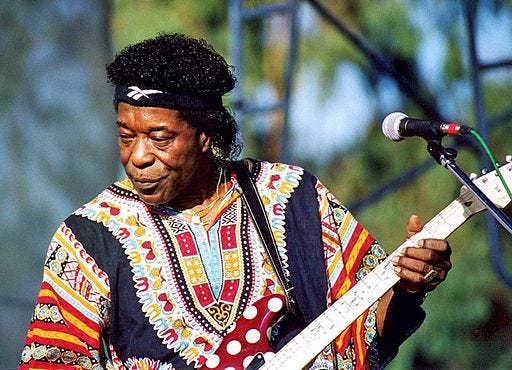

The most common multiple-necked guitars today, of course, are electric. More often than not, if you see one, it will be a double-neck with a 12-string and a six-string. But there are many variations on the theme: guitars with added bass necks, guitar/mandolin combinations, and fretted and fretless necks on the same body, just to name a few.

These instruments are still best used in a live setting when a musician needs to switch between sounds in the same song (for studio work, a double-neck makes little sense), and many musicians have used multiple-necked guitars to great effect on stage over the last 50 years, such as Jimmy Page (Led Zeppelin), Pat Smear (Foo Fighters), and Joe Bonamassa.

However, two musicians, in my opinion, stand head and shoulders above the rest when it comes to playing multiple-neck guitars. These are the people who have not just used a double-neck in place of a mid-song quick-change but have really embraced this type of guitar for the unique instrument that it can be and have created some of the most innovative music with them to date.

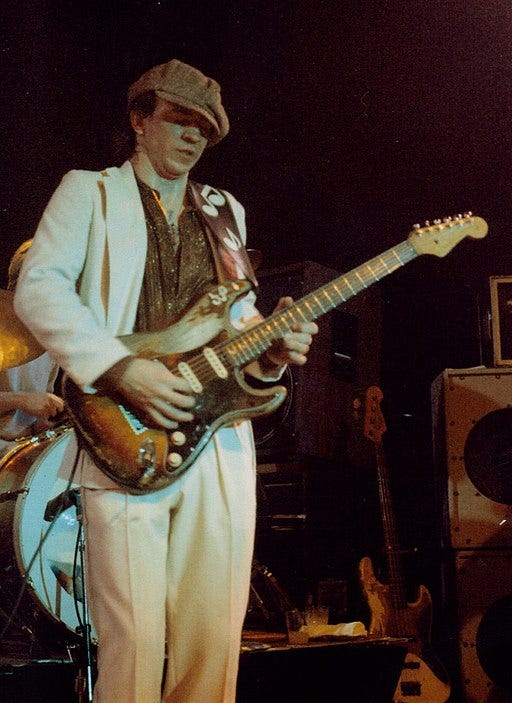

Steve Vai

I’ve written about Steve Vai before, but in just the last few months Vai has partnered with Ibanez to come out with his Hydra guitar.

The Hydra is insane. It boasts three necks — a 7-string and 12-string guitar and a 4-string bass — sympathetic harp strings, and countless knobs, dials, and switches that morph the sound in God-only-knows how many ways.

It’s hard to even know where to begin playing a guitar like this, which is why it is all the more amazing to watch Vai create intricate music with the instrument, which you can do on this video:

Luca Stricagnoli

Now, I have the utmost respect for Steve Vai, but there is one man who can do even crazier things with the guitar. That man is Luca Stricagnoli.

I found out about Luca via YouTube. I was in awe of him the first time I saw him, and I am still just as much in awe of him today. Not only does he play multiple necks at the same time, a la Vai, but he also plays his own backing tracks. He simultaneously mimics a drum set, plays rhythm and lead guitar, and sometimes even whistles or adds harmonica — almost as if to show that what he does isn’t that difficult (for him, at least).

Stricagnoli has a number of different guitar setups that he uses, but perhaps the most interesting and versatile is the three-necked acoustic guitar/bass he plays in the video below.

The future of multiple-necked guitars

Multiple-necked guitars are not exactly commonplace, but they certainly have their place in live music. They have been around for centuries and will likely be around for centuries more.

While many musicians have made use of them over the years, it will be interesting where the next generations of artists inspired by the likes of Steve Vai and Luca Stricagnoli take these instruments in the future.